|

Standard Operating Procedure Engine / Aircraft Operation |

Personnel

Mission Reports

Crew Composition

Intelligence

HEADQUARTERS

303RD BOMBARDMENT GROUP (H)

APO 557, U.S. ARMY

15 October 1944

- BEFORE STATION TIME:

- Check Form 1A and discuss all entries thereon with the Crew Chief and Engineer. Make sure you have the required amount of fuel. Check each position personally. You instill confidence in the crew by this interest, even if you don't find anything wrong. Check the loading of your aircraft and make sure all weight is moved as far forward as possible.

- STARTING ENGINES:

- To standardize starting procedures, the following method is highly recommended to insure a good start:

- Use the "putt-putt," the auxiliary generator.

- Generators will be off, magneto switches off, master switch on, batteries on, invertors on, control surfaces unlocked, brakes on, fuel booster pump on, props in high R.P.M. position, mixture control in idle cut-off, and cowl flaps open. Turbo controls must be off.

- Crack the throttles about an inch from full off.

- Turn hard primer to No. 1 position and hold it up until the chamber is charged with fuel. The No. 3 fuel booster pump must be on to insure fuel flow to the primer.

- As the starter switch is held in "start," prime the engines three or four times by a hard push on the primer. Be careful not to over-prime before the engine starts to turn over, as this can cause a liquid lock which results in engine failure. Do not use the mixture control before the engine starts; this contributes nothing to engine starting, and it does create a serious fire hazard by flooding the blower section. Use the primer only. The engine will start and run on fuel from the primer alone. It is far better to under-prime than to over-prime, especially on cold mornings.

- Hold the "start" switch on as you push the "mesh" switch on. After the engine is turning over, turn the magneto switch to "both," pump the primer hard but slowly and as the engine starts up, come back slowly on the mixture control to "auto-rich."

- After starting engines, idle them at 800 RPM's until the oil pressure becomes normal, then increase to 1100 until taxi time. This will prevent "loading-up." To prevent engine damage due to cold oil, DO NOT EXCEED 1100 RPM's until the oil temperature is 55 degrees Celsius. Do not close cowl flaps to heat engines up in a hurry; this causes unequal cylinder temperature. Usually there will be ample time for engine warm-up before take-off. In any event, don't take off until engines are warmed-up. To assure proper cooling, "ground run" engines in "auto-rich" and, if possible, head the aircraft into the wind.

- To standardize starting procedures, the following method is highly recommended to insure a good start:

- TAXIING:

- While taxiing, if inboards are cut back and locked, they may load up. This can be prevented by increasing RPM to 1200 for two or three seconds every sixty seconds.

- Make frequent checks of the hydraulic pressure. If the pressure is below 600 P.S.I., something is WRONG: Stop immediately, and find the trouble.

- To prevent damage to superchargers, and wastegates, taxi with turbo control at "0."

- BEFORE TAKE-OFF:

- With the RPM setting of 1600; check mags and generators. Keep turbos off.

- With batteries, generators, and invertor on, turbos should be set at exactly 45" MP, for take-off. (You will gain one inch from "ram air.") While the turbos are being set, decrease the throttles with a smooth-slow movement; thus preventing excessive back pressure from building up in the system.

- Be satisfied with your run-up check, or don't take-off. Switch to a reserve aircraft while there is still time.

- TAKE-OFF:

- You can't remember it all, so USE THE CHECK SHEET.

- Without "jamming" throttles, reach full power as soon as possible. Always use 2500 RPM's and auto-rich mixture.

- During take-off, have your Co-Pilot watch instruments carefully, with special emphasis placed on manifold pressure. If one of more superchargers "run-away," pull back on the corresponding throttle until the manifold pressure is reduced to the desired setting.

- Reduce power after take-off as soon as possible. Don't forget to brake the wheels. Do not fly with brakes locked.

- ENGINE OPERATION:

- More engines are damaged in the climb than at any other time. Keep the mixture control in auto-rich. Remember - your aircraft weight is approximately 65,000 lbs. Excessive fuel consumption (300 to 400 gals./hr.) will be required to lift this weight to altitude.

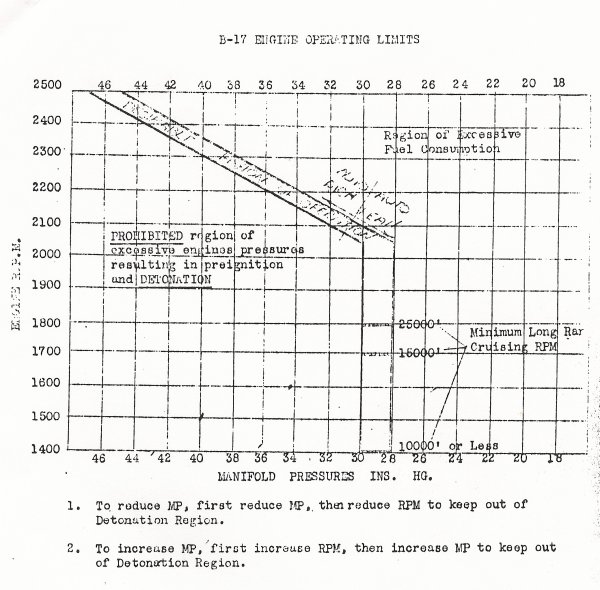

- A chart of engine operating limits for the Wright R-1820-97 is attached. The chart shows three regions of operation. The term "region of desirable operation" is self-explanatory. If you operate outside this region, you can expect the consequences of detonation or excessive fuel consumption. Excessive RPM will not harm an engine, but excessive manifold pressure will.

- Always set turbos with throttles wide open. The B-17 wasn't designed to be flown with throttles at altitude, and thought you must fly it that way in formation, some precaution must remain important. Fly with supercharger controls where possible; it is easier on the engines, and you do save fuel.

- A drop in engine oil pressure at altitude is not abnormal. At 25,000 feet, the oil pressure may be as much as 10 P.S.I. below its sea level value due to frothing (mixing of oil and air). Most aircraft are now equipped with type A-1 fuel and oil pressure transmitters, which have given considerable trouble due to their faulty indications of pressure. A decrease in oil pressure should be accompanied by a rise in oil temperature; if not, you have a faulty instrument reading.

- Frequently the oil temperature on one or more engines may run higher than others during flight. This high temperature is often due to a maladjustment in the oil pressure regulator which operates the shutters at the rear of the oil cooler radiator. If this high temperature stabilizes and is not accompanied by an additional oil pressure drop or rise in cylinder head temperature, it is not serious.

- It is important to keep the cylinder head temperature down, for once they are heated it is hard to reduce. A full-rich mixture will reduce cylinder head temperature without opening to flaps, thus causing additional drag.

- Engine RPM is held in constant by the propeller governor. Often a sudden increase in throttle setting will cause a prop to run-up too high, due to a faulty prop governor. If a reduction of power will not bring the RPM down, it can be reduced by pushing the prop feathering switch in until the desired RPM is reached and then forcing the prop switch out.

- Trouble with engines due to enemy action may frequently necessitate feathering. You must use your own judgement. Be careful not to lose all you oil before trying to feather. You may not be able to unfeather a prop at altitude, so don't feather until you are sure. If you have an engine out and the prop will not feather, there is little that can be done. Place the prop control in low RPM, and if you are not in danger of enemy attack, slow air speed down as much as possible. If the prot continues to windmill at a high RPM, clear all personnel from the nose. It might come off.

- LANDING:

- Sometime before landing, have your engineer make a survey of all the damage which may have occurred; and after the wheels are down have him check the landing gear, with the hand crank, to see that they are all the way down.

- Lower wing flaps slightly at a safe altitude for a check of possible battle damage.

- Check brake pressure and be sure the hydraulic pump is functioning. If the electric pump is out, build up pressure with the hand pump before landing. Very often after a mission, brake trouble may be due to severed lines. In that case, just how much damage or the exact extent of the damage may be unknown, but the Flight Engineer may be able to make temporary repairs.

- MAINTENANCE:

- Write up all malfunctions on the form 1A and explain those defects to the crew chief. Something which seems insignificant to you might cause the loss of an aircraft and crew on the next mission.

- If you have to abuse your engine by overboosting, or running in auto-lean, at high power – REPORT IT! The boys don't mind changing engines, but they can't do it over enemy territory.

By order of the Group Commander

GLYNN F. SHUMAKE

Major, Air Corps

Operations Officer