|

Unusual 303rd Experiences |

Personnel

Mission Reports

Page 1

as published in the Hell's Angeles Newsletter

August & November 1996 and February 1997

[Copyright © 303rd BGA, Hal Susskind, Editor]

On the B-17 My Yorkshire Dream -February 22, 1944, Mission #5 -to bomb Fighter Factory (Aschersleben) Germany. Shortly before reaching the target we were attacked by about 20 FW-190s. On the first contact our tail gunner Bill Werner was hit in the hip, leg and stomach. He was able to crawl back to my position (left waist). I noticed he was not wearing his oxygen mask. I assisted him with my own mask and relocated him forward into the radio compartment where T/Sgt. Wayne Magner gave him first aid. I remained at both waist positions while the other waist gunner, S/Sgt. Sam Ross took over the tail gunners position. Our mission was completed, the target was bombed, and Bill Werner eventually recovered from his injuries.

On the lighter side - 21 days after completing my missions, and waiting to return to the United States on a pass to Northampton, I met a young lady who was working for the British Govt. at Bletchley, Bucks. In May 1945 she became my bride and we celebrated our Golden Anniversary last year. (War is hell - but as they say -you can find some good in everything!!)

Orvis K. Silrum (427) Waist Gunner and Flight Engineer

My most memorable mission took place, Jan. 10, 1945. Our target was Bonn, Germany. I had flown three missions prior to this. This bomb run was fairly routine with only moderate flak. Shortly after 'Bombs Away' there was a loud crashing sound at the rear of the plane, and the nose shot up 45 degrees. My co-pilot, Dave Shroll, and I literally had to put our feet up on the control column to force the nose down and prevent stalling out. We had fallen out of formation far below our bombing altitude of 27,000 feet. My navigator, Tom Donahue, crawled back into the bomb bay to check the damage. He reported that part of the tail section had been ripped off, losing our tail gunner, Marion Mooney.

Naturally we headed West towards France. Visibility kept getting worse. Then my radio operator, Charlie Knowles, saved the day by picking up a call signal from an emergency air field at Merville. I'll always remember the call sign for this radio was 'Martini." We headed for this signal. I was slowly losing altitude. We weren't sure how much fuel we had remaining and it was beginning to snow. We made it directly over the radio signal but couldn't see any runways. It was blanketed with snow. We began to circle and I spotted a fire in a gasoline drum at the end of the runway. I made my approach but wondered if we were too high to land safely. My co-pilot, Dave, said, 'the Hell we are!' and promptly cut the throttles. We bumped down and slid off the runway into the mud and snow, but stopped safely.

We gave our report to the commanding officer of the field and were put up in barracks for the night. Later, I found out that an American fighter pilot at Merville had watched my landing and had written to my commanding officer back at the 303rd Bomb Group recommending the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Two days later we were flown back to Molesworth and began flying missions again. We survived 35 missions, including three to Berlin.

Roy F. Statton (360) Pilot

On my third mission, I was pulled from my original crew to fly in Lt. J.W. Bailey's plane as deputy lead. After briefing I entered the plane via the nose hatch. After our bomb run we had two engines shot out and we fell behind the formation. We were attacked by German fighters. The pilot ordered the crew to bail out, which I and the enlisted crew did. But as I heard later, the pilot and co-pilot remained in the plane for awhile and eventually bailed out into free France.

The rest of us were captured and became POWs. To this day, I have never seen the pilot or co-pilot as they entered the plane via the rear exit.

William Fisher (359) Navigator

Ed. Note: The date of the above mission was 9 Feb. 1945. The target was Lutzkendorf, Germany.

The unusual was normal. I was a 19 year old waist gunner who flew 34 missions before I was 20. I was on 14 combat raids in one month.

My war started when we left the USA in a new B-17 bound for England. We listened to the enemy radio transmissions trying to divert us to the open ocean, as we flew to friendly bases in Labrador, Greenland, Iceland and finally Scotland. We were assigned to Hell's Angels, 303rd Bomb Group. Combat was next.

I was shot down on my second mission with my first alternate crew, (Lt. Mauger). I was hit by flak in my flak-vest, knocked down, losing my oxygen and intercom. I got up, hooked up again and found no blood. I had just resumed to my gun when the oxygen bottle at my feet was hit and exploded, sending the bottle nozzle through the radio room door and striking the radio operator in the leg. Again, no blood. On one and a half engines, the fires out, our pilot made a miraculous, one chance only, wheels down landing, on a just recovered German air base near Eindhoven, Holland.

On our fifth mission, our ball turret gunner was wounded. Unable to help himself, two of us managed to get him out of the turret. I administered morphine and bandaged a nasty wound in his thigh. Forty years later, in Hollywood, Florida, he thanked me for saving his life. Our ship had more than 200 holes, over 100 in the right wing alone. As far as I know, that plane never flew again.

I have emptied my guns while under attack. I've seen B-17s blown up, on fire, mid-air collisions, shot down and friends lost. The smell of cordite at 20,000 feet from German flak was strong even with our oxygen masks on. I have watched many crew members bail out of their stricken plane and tried to count parachutes to tell intelligence later at debriefing.

A German jet attacked alongside our left wing firing at our group leader. He was less than 100 yards away and surprised me so completely, I didn't fire a round. I saw the glider fiasco in Holland, the smoke screens, the fighting on the ground. I watched the German V-2 rockets pass us over the English Channel headed for England, as we carried tons of bombs to drop on them.

A good day got you back to base, a hot meal and shower. Next you cleaned your guns, checked for mail, got some sleep, because four a.m. could start another day over Germany. You wanted to be ready.

Dyle K. Davidson (360) Gunner

The four officers of the Langford crew being wounded in combat was a memorable series of events in my association with the 303rd BG. While on a combat mission to the oil refinery at Hamburg, Germany on June 20, 1944, Lts Donovan (Nav) and Torley (Bomb) were wounded by flak.

On the combat mission, July 20, 1944 to Dessau, Germany, Lt. Langford (Pilot) was wounded by flak.

August 20, 1944 was a questionable date for F/O Zimmerman (Copilot), but he didn't fly a combat mission. It was Sept. 19, 1944, that Zimmerman flew a combat mission to Hamm, Germany. He was seriously wounded by flak. The 303rd did not fly a mission on the 20th.

Four purple hearts being received on the same day (20th) of four months has remained in my memory all 50 plus years.

Donald W. Torley (359) Bombardier

Over Paris in July of '43, picked up flak fragment with our aircraft tail number #341 "Vicious Virgin' on it. 'That was close. It had our number on it.' Developed drop tables on our one and only glide bomb.

A.C. Strickland, Jr. (427) Pilot - also 41 at CW, 384th BG, 545 Sqdn.

By 1940, Antoni Bednarchuk was well on his way to fulfilling his child hood ambition of becoming an aviator. He had already obtained a private pilot's license and attended the Skylines Aviation School in Rhode Island. Toni was also a master mechanic. When he tried to enlist in the Army Air Corps for pilot training he was rejected as unfit; a child hood accident had cost him his left index finger and now a chance of becoming an Air Corps pilot. Ton made his second attempt to enlist on January 6, 1942. This time Toni said he was welcomed with three options; 'it's KP, MP or aerial gunnery." Toni chose the latter. His eventual station on the B-17, 'Sons of Burchs,' was, in his words, 'as far removed from the cockpit as one could be and still be on the same ship...! became a tail gunner."

On December 5, 1942, his B-17 crashed in a remote section of the country, disabling the number 4 engine. Transportation facilities were exceedingly limited; Sgt. Bednarchuk, aerial engineer, working long and uninterrupted hours, with only an engineer's emergency kit and improvised devices, changed engines, installing an engine designed for another type airplane, placed the plane in flying condition."

After the repairs were completed Toni realized his boyhood dream.... he acted as co-pilot on the flight to the base. For his heroic efforts, Sgt. Antoni Bednarchuk was awarded the Legion of Merit, Legionnaire's Degree.

Maysie Bednarchuk [for Antoni Bednarchuk (427) Tail Gunner]

Ed. Note: Toni died in 1990. This report was submitted on behalf of his wife by Alan R. Tortolani, an ardent supporter of the 303rd BGA.

The waist gun position has to be the most useless position to be in when the pilot is doing evasive action maneuvers. It is all one can do to hang on to one of the pivotal guns and be bounced between the ceiling (Thank God for the flak helmet) and the floor. During a momentary halt in one such maneuver during the fighter attack on our notorious 15 August '44 mission, I was able to glance out of the waist window and there, right next to me was a FW190 just as big as life and just on the other side of him was one of our B-17s. Before I could decide whether to fire and probably hit the B-17 too, I was back bouncing off the ceiling again and when I got an other chance to look, the FW190 was gone and I never seen another even at a distance.

Donald H. Foulk (358) Waist Gunner

We had several tough missions, but the one I can never forget is Vegesack. Our Bombardier Jack Mathis was killed and I was never able to relate the story without breaking. The story is told in Harry Gobrecht's book, 'Might in Flight: on page 155. (Also in March 1987 issue of Newsletter)

One other that was a close one. Had I realized I would survive the war, I would have kept a diary. While over the target we had lost two engines from flak. Then shortly after, the pilot Lt. Stouse, had to feather the third, leaving us with one engine. Was a good thing we were at altitude as we started losing it as we headed for home. Fighters tried to finish us, but we fought them off. I think we were lucky as they were getting short of fuel and I was running mighty low on ammo.

Stouse gave us the word to prepare for ditching. He said to stand by and wait for the word. Seemed like an eternity when we spotted the White Cliffs of Dover. Stouse then said we're going to make it. He landed just over them in a field. The aircraft needed lots of repair before it could be flown home.

During this time, our crew flew 'The Eight Ball" on our first raid to Germany. The target was Wilhelmshaven. That's the only picture we have of the "Duchess" crew after that raid.

Eldon W. Audiss (359) Flight Engineer

Our B-17 made it back from a mission but did not make it to Molesworth but landed safely at Little Staunton. Our ground crew with John Simpson, crew chief, was taken there by truck the next day to check it over and replace an oil cooler that had failed. We loaded my tandem bicycle into the truck as well so we would have transportation whenever we needed it.

We got an oil cooler and installed it and a pilot and co-pilot were sent to fly the plane back to Molesworth about eight or nine minutes away. So all our crew, along with the bicycle, got in for the ride back to Molesworth. Coming in for a landing at Molesworth, we came in a little too hard and the landing gear on one side collapsed. I can't remember now whether it was the left or right but the pilot went along on one wheel real good until we lost speed and the wing tip and both props hit the runway and spun us around in a ground loop and off the runway onto the grass where we plowed in a 50 gal. barrel of green paint which gave us a fresh paint job. Everyone of us was O.K., so the crew chief told us to go ahead to 'chow.' So I think it was Othmar Sahli and I got the bike out and rode off to chow. I don't think the airplane ever flew again but was towed into the hangar to reign as "Hangar Queen" Other guys on the crew were: Don Flaherty, Gene O'Brien, Danny Salisbury, Kirkendall, George Hyman, Carl Mohr and Joe Uhis, also Ed Kumer and Milton Grove.

We crewed: 'Shoo Shoo Baby" not the famous one.

Loy E. Tingley (358) Mechanic

With war starting to wind down, there was a shortage of crews available to fly missions - as a result we flew 21 combat missions in 37 days; don't know if that was a record but we do know we had some tired troops. Our last mission was on April 17, 1945 to Dresden.

After having been hit on the 2nd run over the IP and then returning for a 3rd run with fuel running into the bomb bay, we were hit again and this time we developed a wing fire. The crew, in spite of a growing wing fire, elected to continue on to the target and release our bombs. After bombs away, we pulled off to the left of the formation and dropped down a little then bailed out. The plane blew about the time I got out. After capture I was placed in a local jail in a small town called Frieburg. I was there for a couple of days then moved to what seemed to be a farm. From there the Navigator (F/O Bonanno), an Infantry Officer, and I were marched for two days to a place on the Elbe River and were placed in an old fortress (Koenig). There were five American officers there, five Dutch Generals two English Lords - The Earl of Hoptown and the Earl of Haig and the entire French General Staff - I believe a total of 300 officers, lowest rank Colonel along with what I understand was 300 enlisted who served as their orderlies. One day a French General came up to me during the hour we were allowed out of our room and asked if I was the American pilot. I told him I was and he chatted for a few minutes and then asked me if I knew General Marshall. I replied that I knew him by name and he told me he had spent some time with him somewhere and that he was a fine man. I agreed with him. We were liberated by Russian troops the day after the war was over. I might add that was a rather scary event in my young life. Those people looked like they were mostly Mongolians and hadn't bathed for months.

I have always felt that the crew earned some type of award for staying with the plane until bombs away. Two great crew members lost their lives on the ground; the togglier and the tail gunner.

Blaine E. Thomas (427) Pilot

My career was rather uneventful.. I got up early when there was a raid scheduled, helped get the airplane ready to go, then waited four - five or six hours for it to return. Then patch up the holes, maybe change an engine, and have it ready for the next day's mission. I was fortunate that while I was at Molesworth there weren't any bombs dropped on the field. We heard the Buzz Bombs fly over - that is as close as I got - and I'm not sorry about that.

Lester Voth (427) Mechanic

On November 6, 1943 I was fortunate to marry Margery Doreen Colson of Ringstead Northlants who has been my loving and faithful wife to this day.

John M. Hagar (360) Armament Unit

My 23 months as a POW was my outstanding experience. It helped me to mature and learn how to cope with difficulties. In spite of our many hardships, it was a great reaming experience. I spent most of my time studying and exercising walking five to six miles around the compound. This was most helpful when we were marched out of Stalag Luft III in February 1945 just ahead of the Russians. I walked about 80 miles in the next five days. Then we were loaded 60 men to a boxcar designed to hold only 40 men and traveled across Germany with virtually no food and very little water-four days and four nights. Our new camp was Stalag VIII A, and conditions were very primitive with very little food. On April 29, 1945 we were liberated by some of Patton's troops. When the Nazi flag was lowered and the Stars and Stripes were raised on the Camp flagpole, there was a moment of silence followed by tremendous cheers. We were free.

Anthony E. Morse (359) Bombarider

The 29th of December 1944 all of England was weathered in solid and the 8th Air Force was grounded. While lounging in my hut in the 358th Squadron area, I was instructed to report to the Operations Office nearby where forthwith I was offered an option that to this day seems incredible. Capt Lynch informed me that my brother Sgt. Evert Snider, was in the military hospital in Southhampton, England and that a B-17 was available if I wanted to visit him. After trying to grasp what he had just said, I asked him to repeat and explain.

Capt Lynch stated all he knew was that authorization had come from the 8th Air Force. He said all of England was grounded, but if I wanted to try getting in some place take the Captain, who was our Squadron Supply Officer and a rated pilot with me as co-pilot.

I asked what should be done with the plane and when I should return. He told me to leave the Captain with the plane and they would pick it up later. There was no date for my return, but they would need me when the weather lifted.

We took off in the soup and called Darky for a heading to a British Field near Southhampton. When we approached the field on a runway heading and requested a flare at the end of the runway, we were curtly advised that we had been refused clearance to land as the field was closed. There were no options, so I advised we were making a 360 and coming in. They fired a flare and we landed under a very low ceiling.

I hitched a ride to the hospital and walked in to surprise my brother just after the evening meal. OH! What a reunion! I found him well. My family had received no mail from him since before my departure for the ETO in September 1944.

Evert was in Gen. Patton's 2nd Armored Division. Made the landing in Algiers, went through the Kasserine Pass Operation, Sicily, then to Europe and the breakout at St. Lo and on into France.

Some time later, on the drive toward Germany, he lost two tanks and crews on his last day ahead of the line. He was the last man of his original company and was relieved from combat duty and assigned to supply and transportation bringing materials to the front. Later they screened the support troops for soldiers like him, sent them to the hospital in England for evaluation and rotation to the states.

A Red Cross lady had contacted him in the hospital. He told her he had a brother who flew B-17s and would be in the 8th Air Force. He gave her my last letter from the States with my temporary APO address.

I bunked in the Ward with my brother for two nights and returned to base December 22nd in time to fly the mission on December 23rd to Erhang during the Battle of the Bulge.

Mark one for the Red Cross! Whatever was put into play and why, I have no due, but I will be forever grateful.

Harley D. Snider (358) Pilot

I remember the many planes that came in the hangar for repairs. The first plane I worked on was the 'Vicious Virgin," then there was "The Eight Ball," that I was told was Clark Gable's plane. I worked on "The Knockout Dropper, "Meat Hound," Satan's Workshop, Bow-Ur-Neck-Stevens - and many others too numerous to mention. Many came in more than once, also 'Hell's Angels" and the "Black Diamond Express" Many out there will remember these. Every day was an unusual experience, being a small part of such a big undertaking.

Then there was the camaraderie of working and being with other GIs, and the friends we made. One day while the movie "Command Decisions" was being filmed in part at our base - according to the story line the director, as the planes were returning from a mission, had us line up outside to "sweat" the planes return (which we did anyway) so we had a bit part in the movie. Saw the movie several times after the war and many times on TV. They don't always show that part of the film.

Then there was "D Day" and the night before. We knew something was up by all the activity. I was put on guard duty, on the perimeter track, had a Thompson sub-machine gun shoved in my hand (which I had no experience with) and told to stay there until relieved.

In the early morning hours, just before dawn, I started to hear a roar that kept getting louder and louder then coming from the north, the sky seemed to be filled from horizon to horizon with C-47s each pulling a glider. It was an awesome sight one that I will never forget. After that - and all day the sky was filled with planes of all kinds going in all directions, landing, refueling, reloaded with bombs and taking off again not waiting to take formation. We knew it was the beginning of the end. But not as soon as we had hoped.

Joseph E. Bowman (444th) Sheet metal worker

I wonder if any other B-17 was damaged by a peanut-butter sandwich? Our plane, I think we were flying the "Floose," was hit on one of our early missions in the fall of 1944 by a frozen peanut-butter sandwich. It hit right on the button of the plexiglass nose and put a perfect round hole in the plexiglass. It must have been one of our early missions for us because we still had Lt. Birkenseer flying as Bombardier.

Anyhow, after we left the target, Lt Birkenseer announced over the intercom that we had been hit. Then he told us what it was and where the hole was. At debriefing, he told the officer to tell the other crews to be careful what they threw out. The debriefing officer did not believe Lt. Birkenseer until he first pulled out the peanut-butter sandwich on a hamburger bun and then pulled out the perfectly round piece of plexiglass the exact size of the bun.

We had a bit of a laugh over our 'Combat Damage."

Alan D. Chesney (358) Ball Turret gunner

Late in November or December 1942, a fellow ordnance worker and me were on guard duty at the bomb dump on our field. It was about 4pm. The bomb dump had high coils of barb wire and the only way into the dump was through the only gate - always guarded - into the dump. We were making our rounds, carrying a 30 cal. carbine and towards the end of the dump we saw two individuals dressed like English Hunters with shotguns. We caught them flat footed and ordered them to put their guns down. We knew no one - and I mean no one - was supposed to be in the dump, especially civilians. We don't know how they could have gotten in; anyway we put in a call to the captain of the guards. He came by jeep with an M.P. and took them away. To this day, I do not know how they got in with all that barbed wire and the gate under heavy guard. I did try to find out more about this incident, but I guess it must have been 'hush-hush. Have you ever heard of this?

I would say that in mid 1943, the group was preparing to go on a mission. I was in the Ordnance Section. We loaded the B-17 with 500 pounders. All went well until some gunner from another plane was testing and clearing his guns. In doing so - one of the rounds went off and hit the B-17 we were working on. It hit the gas tank on our plane and set the gas on fire. It didn't blow up, just causing the gas to drip and burn. The main concern was that the bombs were all in their racks and armed. The first order given us was to toggle the bombs and drag them away. This was done and our ordnance team did this. The heat was getting to us but we did manage to drag the bombs away. When this was about completed the fire wagon came and foamed the fire down. The whole plane could of blown up, with everyone around it, with it. Some major came over and gave us a pat on the back!

What about the gunner who cleared his guns? Well as I remember, he was tried for negligence and they found him guilty for not following procedure. He was fined to the tune of $25 per month as long as he was in the service to pay for the plane. How about that!!

Anthony J. Sacco (359) Ordinance

January 14, 1944 - 'Alas Kaput' 'For you the war is over!

It's 10 a.m. at Molesworth, and the overcast lifted. What a beautiful day for a 'Milk Run.' Our three day pass to London would begin at 12 noon. 'Sorry fellows, you have got to go, before London."

Pas de Calais, bomb the V-2 rockets that are devastating London. Bombbay doors open at the I.P., the coast of France. We were in the #2 position because January 11, (Oschersleben) our Squadron lost five of seven on that day! Direct hit in the tail from A.A. All 11 men out (photo man on board). At 10,000 feet, the 'white Cliffs of Dover" are a sad sight if you are hanging in a chute over France!

April 25, 1945 - Yanks and Russians met at Torgue, on Elbe. About 500 POWs in our group made contact that night with the 104th Division (Timberwolves). We were on the Russian side at the river. We informed our guard the next day. They surrendered to us, and walked west to the Yanks!

April 26, 1945 - 'O Happy Day!' I am looking forward to meeting my 'Guardian Angel' to 'Thank Him for 'One Hell of a good job!'

Joseph F. Fertitta (358) Tail gunner

My crew and I flew on the last mission the 303rd Bomb Group flew on April 25, 1945. The target was the Skoda Armament Works in Pilsen, Czechoslovakia. Allied Radio warned the Czech workers to stay away from the factory since it was the target for the day. Fifty-two aircraft were dispatched. The mission to the target was free of enemy aircraft.. Since the target could not be seen on the first run, all three squadrons decided to make another run from a different angle. On the first run the anti-aircraft fire was meager to moderate and inaccurate, but on the 2nd bomb run the anti-aircraft fire was intense and accurate.

A few minutes before the 2nd bomb run, radio silence was broken and a voice gave our altitude, direction and air speed. Then all hell broke loose. I was hit by flak in the right elbow. Several other planes were also hit. My co-pilot flew back to Molesworth. I spent the next six months recuperating. l was very fortunate. l am still well and active.

Jack R. Magee Pilot (360)

We replaced engine on #4 and it checked out perfect. l flew as Engineer. Went down runway and heard a big bang so we aborted takeoff. Went back to hangar and checked out engine and it checked OK. Started down the runway again and took off when a loud bang and engine #4 blew up, trying to get altitude, when #1 caught on fire. It was a foggy day and the runway was hard to see. With #1 feathered and #4 windmilling, we finally landed. Thank God for a good pilot!

Worked on 'Knockout Dropper" when it was first to make 75 missions. Worked on "Old Black Magic' at end of war 129 missions. Didn't lose a plane.

Stanley Jacobs Aircraft mechanic (359)

My crew and I outdid ourselves by almost rebuilding an entire B-17 that had been involved in a perimeter crash and was classified as "Salvage." We did it in only 21 days. In between times, we also did a major repair job on another Fortress.

Walter T. Niemann (444th) Sheet metal mechanic

I think when I worked on the 'Hell's Angels' ship, the original ground crew were sweating each mission because they were due to return to the States.

I believe it was the 48th mission, we were on standby. A new crew pulled up. Fabian, the crew chief, briefed the pilot on our manual turbo controls. They were set with a little extra if needed: red lined at 48 inches. We sweated take off. Manifolds were white on takeoff and we all got concerned.

It was after mess, we heard a ship return. It was 'Hell's Angels. It lost two engines and had no compression in the other two. The ship made it home. The ground crew got to go home on a bond selling tour. I transferred to another crew.

Albert J. Orth Mechanic (358)

The Keith Ferris 25' x 75' mural on the Boeing B-17G Thunderbird is of extraordinary significance to me. I was the Flight Engineer on George McCutcheon's crew manning the top turret as I did throughout my tour of duty (36) missions flying out of Molesworth, England during WWII.

The 358th Squadron, 303rd Bomb Group put up twelve B-17s and the 427th Bomb Squadron put up one B-17 to fill out the 39th aircraft that the Group put up for the raid on that mission. Just as the book, the "National Air and Space Museum" states, our bombs had been delivered and we were headed for home when I reported to the crew, "50 bandits at 6 o'clock" and ordered Russell Kinsman, our Tail Gunner to commence firing. I did likewise. The German fighters flew right into our formation, destroying nine of our thirteen plane squadron. Only four aircraft, of the low squadron, resumed to our base at Molesworth.

I have a vivid memory of a FW190 just off our port wing-tip, my twin 50s were pointed directly at the German pilot. I could not kill him for fear of shooting a B-17 directly in my line of fire. He rolled over and headed for the earth. I have no idea of what happened to that pilot. He had managed to hit our outboard engine on our port wing. In retrospect, had I killed that pilot I might not be writing this letter.

It is a devastating sight to see a B-17 aircraft on fire from wing-tip to wing-tip. The Germans had a field day. I firmly believe that our firing at the 'bandits' early in their attack kept them from shooting us down. We all lived to fight another day. Our crew consisted of Lt. George McCutcheon, Lt. R. L. McGilvray, Lt. Fred Kiesel, Lt. Ben Starr, Russell Kinsman (TG), James Aberdeen (BTG), John Alexander (RO) and John O. Burcham (E).

This explains the significance of the beautiful mural to me and my family.

John O. Burcham Flight engineer (358)

16 March 1944 - Raid to Augsburg. Last plane out of Germany, tons of FW-190s hit us. I counted 30 queue up on our plane and attack; 20mm hit radio room, knocked out radio and wounded T/Sgt. Gaylord Geisman (RO). Sgt. Cole kept him from floating out of the radio hatch during evasive action. Without communications, I was unable to keep crew aware of incoming fighters. I destroyed one FW and damaged another. We were under fighter attack for better part of three hours. Without communications I was not aware of crew members or condition of aircraft, every time plane went into evasive action, I would consider leaving, but felt each turn of the props meant less miles to walk home.

Marvin Edwards (360) Tail gunner

Washington's birthday was no holiday!

Our flying position in the formation for the 22 February 1944 mission to Aschersleben, was tail-end Charlie. We had a bombbay full of propaganda leaflets and not bombs.

En route to the target we were hit with flak and fighters. We lost an engine and could not keep up with the formation. We dropped our load over Germany and tried to return home.

On the way back an Me109 picked us up over The Netherlands and put a 20mm. in the waist. Some of the crew were wounded and two men bailed out. The rest of us crash landed near Utrecht. Bob Hannon, the radio operator, and I walked for days before we were able to get help and were able to make contact with the underground. Some of the many places I recall staying at were Magen, Breda, Oss, Erp, Heerlin and Liege. Some of the people we stayed with were Thea, Hara, Gerard, Antoinette Otten, Nicholas and Francois Semoine, Joe Smit and G. Sangen.

Joseph DeLuca (360th) Bomb. (Lt. Crook's crew)

Shanghaid to the 305th

Being assigned to lead crew (Lt. Charles E. Johnson crew) every member of our 427th crew was restated to the 305th Bomb Group at Chelveston, England, where we would get an early morning wakeup to fly to Molesworth for briefing and then lead the 303rd on missions. Being called for a special night leaflet raid on July 20, 1944, the day of the assassination on Hitler, we were told we had 50 fighter aircraft for support for our three B-17s.

Records back up this odd mission because one P-51 was lost that night. Weather conditions were very poor. I flew tail position and could hardly see our two wingmen because of rain and fog. It was a most memorable mission.

Flying two raids on D-Day and seeing the invasion fleet from the air. The 303rd had a perfect hit on a railroad bridge near the beachhead.

Aircraft flown: "Flying Bison," "Miss Lace" and "Sweet Rosie O'Grady." I also took part in "Operation Grapefruit" GB-1, glide bomb raid.

Note: Due to relocation to the 305th, it appears my serving records may have been transferred there. The 303rd "Might-in-Flight" has no record of me in it. But does list other members of my crew. Any help in tracing my records would be helpful. I have contacted the 305th Historical Association but no reply as yet.

Alfred Hollritt (427) Gunner

Ed. Note (Hal Susskind): Your story sounds very familiar and I empathize with you. Soon after our 17th mission to Lechfeld, on March 18, 1944 our crew was informed that since we had lead crew potential we were being sent to a newly organized PFF squadron pool with the 305th Bomb Group based at Chelveston. In the wee hours of April 18 after a month of training, we were alerted to lead the 303rd Bomb Group on a mission to Oranienburg deep in Germany. We arrived at Molesworth with our radar equipped aircraft to lead on the mission but we were informed that we weren't qualified to lead, but with an insertion of personnel from the 303rd we flew the mission. On May 24 we flew as deputy lead to the commander of the 384th Bomb Group on a mission to Oberpfaffenhofen. We got the hell shot out of us and the 384th Group personnel were awarded the Presidential Unit Citation. Our crew got zilch. On May 8, we led some outfit to Berlin; on May 13 we led the 379th to Stettin; on May 19 we led someone to Berlin and on May we went back to Berlin leading someone else. None of these are mentioned in the "Might in Flight" book. I have an official record for my first 17 missions. I got nothing official for the next 24. So much for the record keeping of the 303rd, especially the 359th Squadron. Now you know why I said I empathize with you. But the name of the game in 1942-45 was to win the war and that is what we did.

In the Control Tower

I was assigned to the 303rd in September '43 as a Flying Control Officer having arrived in England a year earlier with an Observation Photo Reconnaissance Squadron. After requisite training at an RAF School and on an RAF airfield in Flying Control procedures, I was commissioned and certified as a Flying Control Officer. My stay at Molesworth was for approximately a year when I was reassigned to 1st Division Headquarters to help in Flying Control at Division level. Compared to combat crews who were putting their lives on the line almost daily, my experiences might appear almost uneventful, but I still had a deep satisfaction when I was able to assist pilots and crews to get back safely on the ground in spite of miserable weather much of the time. Aircraft were often crippled running low on fuel, had serious wounded crew members and need and priority in landing.

Several experiences at Molesworth remain indelibly etched in m memory. I saw the extensive damage to our aircraft after the October '43 Schweinfunt raid, with one 303rd B-17 lost and 15 others barely able to make it back, and learned that 6 B-17s of the 1st and 3rd Bomb Divisions did not make it back. After waiting in the tower with squadron and group personnel on 11 January '44, it became evident that number of our aircraft were not going to make it back from the raid over Oschersleben. The grim new was that 11 of our aircraft did not return. One could feel the dark and somber mood that settled over the base for the next 24 hours.

I'll not forget the day when I was on duty in the control tower, 20 February '44. Some of our aircraft were already back from the mission to the Leipzig area when we were alerted to the fact that an aircraft from the 351st BG was trying to make a landing at Molesworth. The flight engineer, Sgt. Archie Mathies and Navigator, Lt. Walter Truemper were flying the plane because the co-pilot was dead and the pilot gravely wounded. They had been ordered by their CO to bale out with the rest of the crew but Mathies and Truemper wanted to try to land the aircraft because the pilot was still alive. When they tried to land at Molesworth they were getting instructions from another 351st aircraft trailing them. They had to pull up because they had gone the whole distance of the runway an were still about 15 feet in the air. We learned shortly after, that the had crashed when making an attempt to land at another field. Mathies and Truemper were awarded Medals of Honor posthumously.

I was on duty one night about 1900 hours when I received a call from the 455th Bomb Group, 2nd Division. One of their B-24s had landed at Molesworth earlier in the day and the aircraft was needed for a mission the next day. They wanted to send another B-24 with extra crew to pick up the aircraft. They asked about our weather. It was marginal but we were open at the time. They decided to send an aircraft. Within about 35 minutes when they arrived over the field, the fog, which was now blanketing most of England had closed in over our station as well. They could not see our runway lights. They spotted our field when we shot rockets to penetrate above the ground fog. By this time there was no place to divert the aircraft as dense fog was now covering all of England. The aircraft kept circling as we had our Flying Control ground crew try every kind of flare and landing aid we had in arsenal. We finally tried magnesium flares which was the latest kind of aid that had been issued to us. That was a mistake because the light was so brilliant it diffused through all the molecules of fog. The pilot was making a rather steep descent and was blinded by the utter intensity of the light. I could see the aircraft in steep descent over the runway and told him to "Pull up, Pull up" which he did, just a few yards above the runway. We extinguished the magnesium flares. (Sodium lights were not yet being used, or at least were not available to us). Then, using nothing but the runway lights and fire pots to mark the end of the runway, the pilot made a very cautious approach and set the plane down safely. When he came to the tower to call his home base it turned out that he was Jimmy Stewart's roommate. We now had two B-24s at Molesworth which would not take part in the next day's mission.

On another occasion while making a physical inspection (in a jeep) of our main Runway early one morning, and with limited visibility, I discovered a truck loaded with bombs at the intersection of our two main runways. The truck had a flat tire. The driver had not reported the incident to the tower, nor had he asked permission to cross the runway at night. I returned to the tower, put the field on "Red" until necessary repairs were made and the truck removed. I later discussed the incident with the motor-pool officer and the driver of the truck. It turned out that the driver's name was also "Johnson."

Another incident that is still quite clear in my memory was the occasion when two practice bombs hit our field one night while I was on duty. It happened - 6 July 1944 two or three days before the visit of the King and Queen to Molesworth. In the tower we always monitored the frequency used by the RAF when they were executing their practice bombing nuns at night. The bombing range was apparently 15 miles or so, northwest of our field. When the bombs were released the bombardier would transmit - "Number one bomb gone, Number two bomb gone." We were accustomed to hearing that almost every time we were on duty. On this occasion we had one of two of our aircraft doing some night flying and therefore had our runway lights on as well as our ID circle of lights directly in front of the tower. Seconds after I heard "Number one bomb gone" I heard an explosion and "Whoom." "Number two bomb gone," followed by another explosion and "Whoom." The first practice bomb had hit behind the tower and a little toward the main hangar. The second practice bomb went through the roof of the main hangar. The British bombardier had mistaken our ID lights in front of the tower as their night bombing range. I immediately called the RAF Operations people and advised them of this rather serious "deviation from course" of their aircraft. They apologized and sent out someone to investigate the incident two days later (when the King and Queen and children were on the base). I should be thankful that bombardier missed the tower by about 50 feet.

Once in a while when on duty some pilot would give us an extra thrill by buzzing the tower. One day while two P-51s came low across the field and buzzed the tower, they went around a second time and dropped even lower. This time they peeled off, lowered their gear and landed. The first plane had hit the deck with the tips of his props, which were bent back, and the airscoop was flattened. The pilot had been slow-timing his engine. He came to the tower and called his CO and very meekly described his mishap. I never heard whether the pilot was disciplined or not, but that was a low buzz job. I was proud to share a year of my life with some of the most skilled and courageous pilots and crews of the 8th Air Force. I had six or seven flights in B-17s, two to the continent in the last months of the war.

Robert L. Johnson (3rd Station Complement) Tower Operator

Unusual is putting it mildly!

On March 10,1945 while on a mission to Schwerte, I was in the high plane in the low squadron which put me next to the low man in the lead squadron - if my leader positioned himself right. For some unknown reason he flew in too close which put my right wing in the prop wash on the low man in the lead squadron so I had to continually be correcting that situation. But on the bomb run my leader pulled in even more which put me just behind and below the low man in the lead squadron. About that time his trailing antenna started coming out, which is a lead ball on a steel cable, I didn't like the idea of the cable wrapping itself around one of my propellers as that lead ball was directly in front of me so I just dropped back as it came out. When it was about 100 feet out there was a burst of flak directly ahead but between the planes and the antenna was gone so I pulled back up in formation and we went on home. When we landed my engineer looked that plane up that was ahead of us in the formation to ask why he put the trailing antenna out on the bomb run and he said he didn't so they went out to the plane and looked and the antenna was gone! So who turned that switch "on" to push me back so I wouldn't be where I should have been when that flak came up and exploded? I call it Divine protector!

While resuming from a mission - I don't remember which one - I was overcome with one of natures urgent calls with no provisions on board for such emergencies. The only solution was the bombbay! The togglier opened the bombbay doors and I went back and straggled the narrow catwalk and hung on to the bomb rack and let nature take over and got relief! Where its destination was has never been determined!

Clyde Henning Pilot (358)

How fast is fast?

My most memorable experience as a member of the 360th Bomb Sqdn., happened on the mission to Hamburg on 20 March 1945. I was "togglier" on Lt. Larry S.Tyler's crew. We encountered heavy flak on the bomb run. Just as I said, "Bombs Away" Lt. Tyler started our turn away from the target, when B.J. Hamm, our co-pilot called out, "Me210s at three o'clock." I looked out and saw the planes streaking ahead of us and said, "Those aren't 210s; they are Me-262s, the German jet fighter." They harassed us all the way out over the North Sea. They were awesome as we could not track them with our turret guns. They were too fast. "A scary mission."

Note: Throughout my WWII career, I never lost an aircraft recognition test. The night before the mission noted above, I had visited the Intelligence Office and saw pictures of Me-262s for the first time. I shall never forget that mission!

Leroy Faulkner (360) Togglier

Making one out of four!

Making one out of four!I believe my greatest achievement was assembling a complete B-17 plane from four planes that had crashed; after completing the assembly, the officer asked me if I was ready to preflight it. My mind immediately focused on every connection of cables, bolts, screws, etc.. I replied, I'm ready to go " The flight was a success."

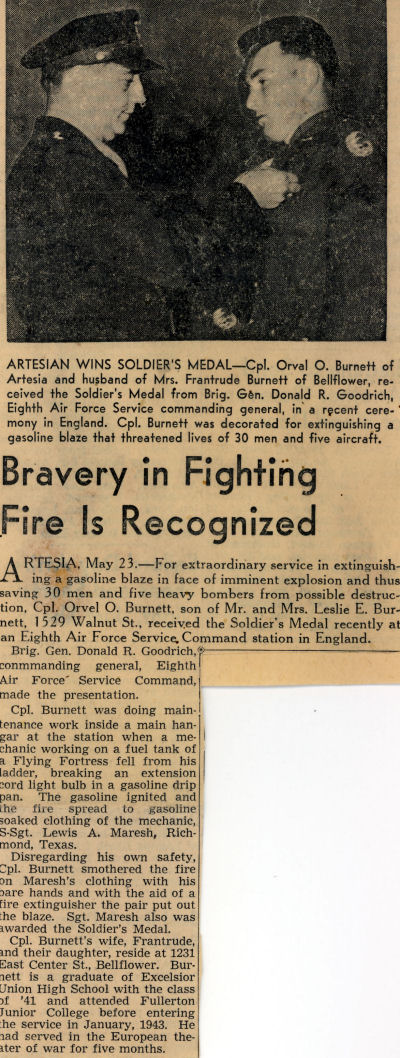

An unusual experience: we were removing gasoline tanks from damaged airplanes and a lot of gasoline spilled on the floor and as I was removing the overflow tube, my foot slipped on the stepladder and I fell. I hit the floor in the gasoline, my trouble light broke creating a spark igniting the gasoline and I was on fire. I ran about 30 feet to a dry floor, fell down and began rolling.

Everyone ran out except Burnett. He helped put the fire out on me. I then asked him to grab a fire extinguisher and I took one. I said, "Let's fight it." We both worked until all the fire was extinguished. There were five B-17s in the hangar. Everyone asked me how it happened and why it did not explode. I could not explain it. I realized much later why it did not explode because I called on God. "Lord let it explode."

"It is written call upon me and I will answer him; I will be with him in trouble. I will deliver and honor him. I will show you my salvation, (deliverance) Psa. 91:15-16"

The B-17 bomber we assembled from parts of damaged planes (we called the boneyard) was originally camouflaged is described as follows; one wing was camouflaged, one silver wing, one half of fuselage was camouflaged and one half silver. The tail section was also mixed in color. It was an outstanding plane in the sky and a very satisfying accomplishment. When on vacation in Washington, D.C. a few years ago, I saw a B-17 in the museum and I had great respect for it and a feeling I cannot explain.

The years I spent in Service for my country is a chapter of my life which is an experience that is gratifying to me. I have fond memories of the men who were cooperative and worked so diligently to accomplish our tasks.

Love you guys!!

Lewis (Shorty) Maresh (444) Repair Chief

Frankfurt, 29 January 1944

My position was the right waist gun. The mission was Frankfurt, Germany on Jan 29, 1944. Our pilot, Lt. James Fowler and co-pilot, Lt. Barney Rawlings were flying "GI Sheets," the same airplane we flew on our first mission to Emden on Dec. 11, 1943. This day we had problems with the No.2 engine supercharger, but agreed to continue the mission. Everything was fine until we got within sight of the target. We had to feather the No.2 engine due to an oil problem. "GI Sheets" could not keep up with the group with 2 1/2 engines, so we became a straggler and a target for enemy fighters. The first wave of four Me-109s attacked us from the front. The bombs had been jettisoned. The fighters did a lot of damage even though the pilots took evasive action. This was my first experience with zero gravity. One shell went through the nose plexiglass causing serious injury to the bombardier and navigator. The explosion had knocked out the oxygen system, the instrument vacuum system and damaged some headset communication. We dove for cloud cover which was about 5,000 feet. Utilizing the cloud cover as much as possible allowed us to get back over Belgium. There the cloud cover ran out as we flew over a large FW190 fighter base. They not only sent up fighters but fired on us with small arm weapons. The combat with fighters was futile. We lost most of our gunnery protection and was receiving extensive damage to our aircraft along with injuries to the crew. I had received several fragment wounds including one to the head that required a compress bandage to stop the bleeding. At this time the ball turret gunner took over my position. With the rudder control out and No 3 engine on fire, the pilot decided we had enough and sounded the warning bell. It had been approximately two hours since our first attack which made it about 1300 hours. The sounding of the warning bell apparently got my attention. I looked over the situation briefly and decided the airplane was going to crash. After jettisoning the waist door I jumped out. It was then that I realized how low we were. I estimated to be less than 400 feet. There were two quick jolts, one when the parachute opened and shortly thereafter when I hit the ground. Fortunately I landed, burying half my body in a soft spot of a grassy area I was the only one to bail out. Jim and Barney did a super job of crash landing the airplane in a small clearing a few kilometers from where I landed.

A Belgium patriot who happened to be in the area came to me and pointed to where I should hide. Later when it was dark, he took me into his home. I must have been a sorrowful sight. The women of the house gasped when they saw me. One of the women removed superficial shrapnel and cleaned the wounds. The next morning this Belgium friend put me under some hay in his one horse drawn wagon and took me to the first of eight places I stayed until liberated by the Americans, eight months and 6 days later. The hiding and running period is another story.

Loren E. Zimmer (427) Right Waist Gunner