|

427th Barrat Crew Robert J. Barrat, Pilot |

Personnel

Mission Reports

ROBERT J. BARRAT CREW - 427th BS

(crew assigned 427BS: 22 Nov 1944 - photo: Nov 1944)

(Back L-R) S/Sgt Matthew Lazarowicz (R-KIA),

2Lt Dean Harvey (CP-KIA), 2Lt Robert J. Barrat (P-KIA)*,

F/O Shirl P. Best (N-KIA)*, S/Sgt William T. Karp (Tog-KIA)*

(Front L-R)

Sgt Herbert D. Link (WG-KIA)*,

Sgt Louis N. Linhart (BT-KIA)*,

S/Sgt Raymond F. Reiss (E-KIA)*,

Sgt George H. Emerson (TG-POW)

* Joint grave marker - Jefferson Barracks Cemetery, St. Louis, MO

(KIA-POW) On 09 February 1945 mission #313 to Lutzkendorf, Germany in B-17G #43-39149 (no name) (427BS) GN-D. Two 427th BS B-17s collided before "bombs away" - #43-39149, piloted by Lt Barrat (8 KIA 1 POW) and #42-31060 Pogue Ma Hone piloted by Lt A.K. Nemer (5 KIA, 1 POW & 3 Returned). The right wing of #42-31060 hit the tail of #42-39149. The rear part of the fuselage of #42-39149, from the waist window back, was torn off and the B-17 was seen going down in two sections. The sections hit the ground and exploded. Miraculously, Sgt Emerson (TG) managed to parachute out of the severed tail and became a POW. All other crewmen were killed. In 1991, a German eyewitness to the crash of #43-39149 reported that the aircraft was heading for the center of the village of Eisenberg. Just before it would have crashed into the city, killing hundreds of people with its intact armed bomb load, Pilots Barrat and Harvey managed to level the B-17 and dropped their bombs on a field outside the village. Only one house was hit that killed 10 people. It then crashed and exploded in a wooden area near Eisenberg / Thuringen, Germany. In October 1991, a group located the crash site, recovering parts of the aircraft and the human remains of the crew members. A gold wedding band with the initials "MN to PB 1944" was found that belonged to Navigator F/O Best. Another ring with the initials "R.J.B." was found that belonged to Pilot 2Lt Barrat.

(KIA-POW) On 09 February 1945 mission #313 to Lutzkendorf, Germany in B-17G #43-39149 (no name) (427BS) GN-D. Two 427th BS B-17s collided before "bombs away" - #43-39149, piloted by Lt Barrat (8 KIA 1 POW) and #42-31060 Pogue Ma Hone piloted by Lt A.K. Nemer (5 KIA, 1 POW & 3 Returned). The right wing of #42-31060 hit the tail of #42-39149. The rear part of the fuselage of #42-39149, from the waist window back, was torn off and the B-17 was seen going down in two sections. The sections hit the ground and exploded. Miraculously, Sgt Emerson (TG) managed to parachute out of the severed tail and became a POW. All other crewmen were killed. In 1991, a German eyewitness to the crash of #43-39149 reported that the aircraft was heading for the center of the village of Eisenberg. Just before it would have crashed into the city, killing hundreds of people with its intact armed bomb load, Pilots Barrat and Harvey managed to level the B-17 and dropped their bombs on a field outside the village. Only one house was hit that killed 10 people. It then crashed and exploded in a wooden area near Eisenberg / Thuringen, Germany. In October 1991, a group located the crash site, recovering parts of the aircraft and the human remains of the crew members. A gold wedding band with the initials "MN to PB 1944" was found that belonged to Navigator F/O Best. Another ring with the initials "R.J.B." was found that belonged to Pilot 2Lt Barrat.

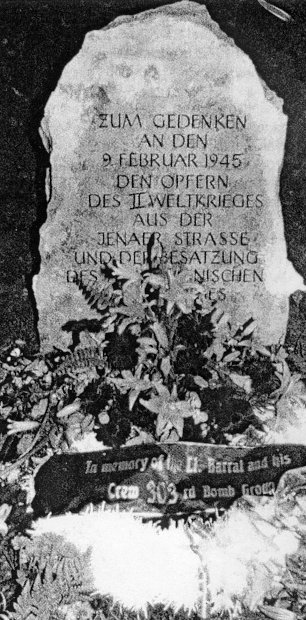

On 07 September 1995 villagers erected a memorial to the crew members who reportedly gave their lives to save hundreds of villagers. Surviving crewman George Emerson (TG) attended the dedication. Lt Barrat's ring was presented to his two sons and sister. F/O Best's ring was carried back to the USA by Hal Susskind, Editor Hell's Angels Newsletter who later returned it to F/O Best's sister. The memorial was the first instance where German citizens honored American Airmen.

by George H. Emerson

|

An empty bunk existed in the barracks. I suggested to Elden that he stay the night. He accepted. Another normal evening, lights out at 9:00 P.M. Next morning, lights on at 3:00 A.M. awakened the Barrat crew: Emerson, Karp, Lazarowitz, Reiss, Link, and Linhart. The officers, Barrat, Harvey, and Best, slept in different quarters, but were awakened the same time. I donned my clothing for the mission, consisting of long underwear, suntans, regular shoes, electric flying suit, fleece-lined flying suit, fleece-lined boots, flak jacket, and parachute harness. In jest, I suggested to Elden that perhaps he should accompany us on this mission. His answer was, “No.” My reply, was, “Probably best you not go. We could be eating dinner with the “Jerries” (Germans) tonight. (As it happened, I was with the “Jerries” that night, but no dinner).

On to breakfast, briefing for the target, and to our B-17 #4339149 - no name for this mission. We carried ten 500 pound bombs for this mission.

Take off. Formation into squadrons and groups was normal, then on to our target, an oil refinery near Lutzkendorf, Germany. We had donned oxygen masks at 10,000 feet as we progressed to an altitude of 25,000 feet. As we neared the target, anti-aircraft fire was visible. From my position, I could see very well to either side, but not above. I became alarmed when hearing excess propeller noise above our aircraft. I radioed the pilot. He in turn called the upper turret gunner (Reiss) to verify my alarm. His vision would be much better than mine. Reiss was terrified. No one could understand his answer. Suddenly, a loud and turbulent noise. I was being tossed around like a ping pong ball. I fell from the severed tail. I awakened sometime later. My parachute was open, but who pulled the ripcord? I could never remember. My oxygen mask was still in place. Blood was trickling down the hose. No pain, however. Lack of oxygen made me drowsy. The earth looked far away. I dozed again. I awakened to see the earth rushing up. This being my first jump, I worried about a proper landing. I accidentally landed properly with my back to the wind. However, the breeze slammed me and dragged me a few feet. I had landed in a plowed field, which had somewhat cushioned my fall.

Unbuckling the parachute, I glanced into the distance to see many people coming my direction. I ran the opposite direction, but when bullets started landing nearby, I decided this wasn’t a good choice. I was scared as hell. My decision was to walk toward them, hands in the air. As we met, civilians encircled me. These included men, women and children - armed with farm implements and guns. Some were shouting in German, two words I understood well: “Chicago Gangster!” Hitler had informed his people all airmen were recruited from Chicago, and all were former gangsters. I also understood their motions: They wanted me to take off all clothing down to my underwear. They shredded the fleece-lined flying suit, and electric suit to see if I might have maps or weapons hidden within. I then was allowed to put the bare necessities back on.

The next set of gestures I also understood to mean they wanted me to start walking toward the nearby village, with me leading and them following. I was spat upon and repeatedly kicked in the rear. One particularly angry fellow aimed his rifle at me. As he pulled the trigger, another person hit his arm, causing the bullet to rifle into the sky. Apparently lots of blood had covered my face as a result of the crash. I could see remorse in the faces of women in the group.

Upon reaching the village, I was locked in a garage. My imagination ran rampant. I imagined a hanging was in my future. A few hours later, the door was opened by a policeman. He motioned for me to march ahead of him on a dirt road leading from the village. He would ride his bicycle, I would walk ahead. Eventually we were overtaken by a farmer and his small wagon which was powered by a bull. The policeman motioned for me to push his bicycle. He would ride in the wagon with the farmer. As we came to the city of Eisenberg and entered the police station, I observed many curious laborers around the station. All had on wooden shoes and not much clothing. I was taken upstairs by a guard, shoved into a one room cell with no lights, bedding or furniture.

After dark, I heard voices outside my cell, the sound of wooden shoes, and a prying on my door. Lots of shouting. I could understand only one word: Essen. I was thinking these people wanted to know if I’d ever been on a bombing mission to the city of Essen. I just knew these people wanted to hang me. Then I heard wooden shoes scurrying away from the door and moving down the hall. The door opened. A German guard appeared, checked me out, then closed the door. Again, the voices returned, followed by the clatter of wooden shoes, and once more a prying on my door. Then I heard the sound of wooden shoes scurrying down the hall just as before, then silence. The door opened again, and the same guard checked me out again. I began to think these people were trying to help me. No more activities in the hallway that evening. However, I heard a noise outside a small window opposite the door. I peered up as far as I could. I saw a loaf of bread was being lowered from a room above. The string it was being lowered with was fully extended. I tried my best to reach it, but couldn’t do so. I then connected the people activity in the hallway with the bread incident. This gave rise to a good feeling - these people were trying to help me. I also believe these people were the same ones I saw as I entered the police station. No more activities this night. No sleep either. Later, as I learned a bit of German language, I discovered the word essen also means eat. This confirmed the people in the hallway who had been shouting essen really had been trying to help me.

Next morning, I was taken downstairs to police headquarters, interrogated and shown scorched parts of my aircraft, including oxygen tanks and other miscellaneous parts. I was also shown scorched I.D. tags of some of my crew members. Although I suppressed my emotions, this confirmed my suspicions. I might be the only survivor of my aircraft.

Sometime later, a high ranking German officer appeared. He motioned for me to follow him to his waiting car. His girlfriend occupied the front seat. The rear door was opened for my entrance. I knew not where we might be going, but remember coming to the town of Erfurt. This city was on the target list the same day of my accident. Numerous streets were blocked by damaged buildings. People were picking up personal belongings in wheelbarrows. It took some time to navigate around closed streets. All the while I felt guilt feelings. This was the first time I’d seen the results of a bombing raid on a city.

The driver eventually made it around the city. We were traveling again. A few hours later we came to a stop at a place called Oberusal, an interrogation center. All airmen had heard of this place in training sessions. I was taken inside, introduced to someone in charge, and then whisked away to a very small cell. No water, no toilet. A wooden bed with straw for mattress. A bell to ring in case of emergency. Next morning, the door opened. I was given a bowl of soup and a slice of German black bread. I was then led down the hall to a toilet, and then back to my cell.

Next morning, the same program, but after getting back to my cell, a guard stopped by to interrogate me. His English was excellent. He wanted to know where I was stationed in England, what bombing mission I was on when captured, routes taken to the target, etc. My answers were name, rank, and serial number. The Geneva war commission rules stated, this would be all a P.O.W. needed to divulge. Speaking of regulations, I could have legally been killed when captured. I had failed to wear my “dog tags,” my identification tags, on that fateful mission. On the fifth day, I was promised more food if I’d cooperate. I gave it serious thought, but I didn’t cave in. The seventh day, the interrogator entered as usual, but asked no questions. He informed me he already knew the answers to previous questions asked. He proceeded to prove this from a large folder he carried.

On the ninth day, the cell door opened. A German soldier motioned for me to follow him. We arrived at the train station in Oberusal a few minutes later. We boarded a train going somewhere, I knew not where. While en route, I was allowed to visit the restroom. The mirror within showed my blood-spattered face. I cleaned up a bit. A cut was visible between my eyes. As I emerged, two German nurses noticed me. They volunteered to treat my wound. I accepted the offer. This was the second friendly gesture I had experienced since capture. A few hours later, the train stopped. I was escorted to a waiting vehicle, then to a German army base headquarters. Three German army boys about my age were on duty. One could speak English. I noticed a painting of Adolph Hitler hanging on the wall. I was asked if I knew who it was. I nodded my head, and was asked what I thought of him. Realizing my perilous situation, I answered that I had no opinion. I was also asked about Hollywood, the movies, cowboys and Indians. Were Indians still roaming the prairies, chasing the cowboys? I was surprised these soldiers were interested in such things.

Later, I was picked up by two German Air Force boys and taken to a prison called Wetzler. Wetzler was a transit prison camp for captured United States and English Air Force personnel. I was taken to a barracks, assigned to a space, and left to introduce myself to other American and English Air Force prisoners of war.

This prison was double barbed wire fenced, with guard towers surrounding the perimeter. The floor was your bed. I was issued a blanket, compliments of the Red Cross. All P.O.W.s received Red Cross parcels occasionally. These parcels were delivered to a German warehouse nearby in large army-style white trucks with red crosses on them. Rumor was these trucks came from Switzerland and weren’t to be fired upon by the allies. Parcels contained such as items as soap, cigarettes and such food items as chocolate bars, powdered milk, soap, a processed meat and cheese. The parcels were issued to two people to share, the contents could be eaten pronto if desired. Any rationing to be done was up to you. The parcels were in addition to the scanty rations the Germans provided. The German rations usually consisted of black bread and an occasional bowl of soup.. I was afraid to look at the soup while eating. I’d heard some of the prisoners had found insects. The black bread was quite different. I was sure it contained a bit of sawdust. However, as I became hungrier, it began to taste pretty good. The loaf of black bread was issued to nine men. The division and slicing of the loaf was up to the discretion of the men. One prisoner was appointed to do the slicing. The remainder would watch the division closely. All slices had to be equal.

Every morning at 9:00 A.M., German guards would come through the barracks yelling “Rous Mit!” This meant “get out fast, and be counted!” If someone was missing, dogs would be sent through the barracks to locate and clear stragglers. However, as it happened, I never observed any stragglers.

I’ll never forget some of the injured prisoners in camp. I saw one P-38 pilot with ears missing, eyelids scarred, no lashes and his face totally scarred. The story was that his P-38 was hit, caught fire and burned him severely before he could eject. Another fellow with deeply a scared face explained that his parachute landed in a tree, a very soft landing. Before he could comprehend what was happening, the parachute gave way, leaving him to crash through the many branches below. Every prisoner had a harrowing experience. There was much conversation about capture experiences, some had witnessed gruesome scenes, such as airmen being hanged by the neck at railroad stations.

A favorite subject, of course, consisted of talking about food at home: steaks, hotcakes smothered with syrup, baked potatoes etc.

One day there was an unpleasant incident. I didn’t witness it, (I’m glad I didn’t), but I was told of one prisoner who became so despondent, he climbed the fence broad daylight. He was shot and killed by prison guards.

I frequently walked the perimeter of the camp to exercise and kill time. After about three weeks at Wetzlar, we began hearing artillery fire. The allies must be getting close, we thought. We all hoped the camp would be liberated by the allies. No such luck.

We were awakened early one morning, ordered to form columns, follow German guards to the railroad station in Wetzlar, then ordered to gather in waiting box cars. Men were seated on the floor, body to body, 75 men per car. The locomotive was a coal burner, steam propelled. We knew not where we were going, or how far. Two guards per car both occupied space near the open door. Traveling was slow. At times, the train would stop in a wooded area. We all knew the reason for this. Allied fighter planes were always looking for moving trains, usually attacking them on sight. On some occasions when the train stopped, all prisoners were allowed to vacate the cars to relieve themselves. When ordered, we would reboard and resume positions. There were two false alarms while en route, – possible attacks by allied fighters. The train stopped. Terrified prisoners and guards went running some distance before sprawling to the earth. During the second false alarm, I was far away from the open door, but I was the first one out. After each false alarm, the reboard call would be made, and everyone would resume their positions.

No matter how dire the circumstances, GIs can and do maintain their sense of humor. For instance, the door was always open, one guard on each side of the opening. Each took turns napping. On one occasion, both guards fell asleep. A prisoner nearby picked up one guards rifle and pointed it toward the other prisoners. Luckily, he didn’t get caught. He placed it back in position before either guard awakened. Another time, a fellow prisoner had traded American cigarettes to one of the guards for extra bread. While both guards were dozing, he carefully lifted these cigarettes from the guard’s jacket pocket. Fortunately, he was not caught either.

The smells within the car were pretty revolting. Some of the prisoners were sick. Others might not make it to the next rest stop. The distance traveled to our next camp wasn’t all that far, but due to the numerous stops and false alarms, much time had elapsed since the beginning of the trip. We finally arrived, disembarked and marched to our new prison. I noticed many large bomb craters outside the perimeter of the prison. This made me wonder how these bombs had missed the camp.

Our new prison was located on the outskirts of Nurnberg. We were each assigned to our barracks and floor space therein. As before, the floor was your bed. A blanket was issued for warmth. There was no heat, and the sanitation was poor. The toilets were the out house type - round holes large enough for one’s rear end, and plenty of foul odors. We lined up once per day for the German rations. Soup was the daily fare, usually potatoes and a vegetable. Sometimes we were given a loaf of black bread divided amongst nine men. As before, we also received Red Cross parcels occasionally, one parcel per two men. I shared my parcel with my good friend Harry Jones. This proved to be a good partnership. I didn’t smoke, he did. I always gave him my cigarettes. He used the extra cigarettes to trade for extra food. Sometimes the guards would trade food for cigarettes. They really liked the American cigarettes.

At least twice while in this camp, air raids were made on the city of Nurnberg. The English bombed the city at night. The sky was lit up from searchlights and exploding flak. There were eerie sounds of air raid sirens and blockbuster bombs striking the city. Our barracks shook from the bombs. Prisoners covered their heads and prayed. The shrapnel from bursting AA shells aimed at English planes, raining down on our barrack, sounded like a hard rainstorm. Fortunately, none of the bombs aimed at the city of Nurnberg struck within the prison.

We were always up on the latest war news. A few English and French prisoners had been prisoners for many years. When on work details, some of them had accumulated enough materials to construct a handmade radio. They’d listen to BBC nightly news. The latest news was passed around person to person. The radios were well hidden, thus the Germans would never find out they had them. The Germans also gave us their version of the news, which was always totally different.

One piece of equipment most prisoners had was something called a “smoky Joe.” This was basically a stove, made from powdered milk cans from Red Cross parcels. Lots of air could be forced through a tunnel by means of a hand-propelled tin fan. The whole phenomenon meant much heat could be extracted from a very small amount of wood. Wood was precious, hard to come by, and sometimes we did have food to heat up. The best way to get your own smoky Joe was just to trade extra cigarettes for it. That’s how Harry and I got ours.

There was plenty of leisure time at this camp, but no exercise area. There was lots of conversation with your fellow prisoners -comparing capture experiences, much talk of the good food you used to get at home, etc. I spent my 20th birthday walking the perimeter of the camp, wondering about the folks back home and wondering what my future might be. Every day, the blasts of American artillery seemed to be getting closer. Once more we concluded we would soon be liberated.

But as before, no such luck. On April 3, word circulated we’d be leaving this camp. An agreement was made with the Germans we would conform and maintain discipline on the march. In exchange, the Germans would make us march no more than twelve miles each day. Red Cross parcels were handed out before starting, as well as a few times en route. I later heard that 10,000 P.O.W.s were on this move. This so-called “march,” was strung out for several miles along the 1st autobahn in Germany. The possibility of escape on this march was an option. However, since we knew about the allies progress, escape attempts were not really a consideration.

The second day out, our column came under attack from our own P-47s. Three prisoners were killed and several more were injured. This happened near my particular position on the march. It is still not known whether this attack was against marching soldiers, or were bombing a nearby overpass. Soon after the attack, someone panicked and yelled, “Attack!” Everyone scattered including the guards. This was a false alarm, but not knowing for sure, to stay in place wasn’t an option. My particular position was in the vicinity of a small town. As we scattered, I ran through a yard, came to a chicken coop, put my head down in hopes of crashing through, but didn’t make it. I was knocked almost unconscious, just sat there till the all clear was given. We reformed. A few P.O.W.s made a sign from towels, and placed it near the column, reading “P.O.Ws.” Their hope was that any future fighter planes might see this.

We continued on our way. No more attacks or false alarms. With the columns covering several miles, on any given night, some prisoners might be in barns, others in churches, and others under the stars. The opportunities for guys to trade cigarettes for food was pretty good on this trek. We encountered civilians along the way willing to barter. On evenings spent on a farm, the potential for trading was good.. My friend Harry did much trading. He and I ate better than some on this trip. On one of the nights spent at a farm, Harry met the farmer. The farmer wanted to learn English, so what did Harry teach him to say? “Buy American war bonds.” And after the farmer mastered this one, Harry motioned for our nearby buddies to form a circle around us. On command, the farmer used his new English phrase. Total laughter ensued. Later on the same evening, Harry traded cigarettes for a chicken. We cranked up the smoky Joe, put the chicken in a pot. I don’t remember where the pot came from, but we boiled and boiled. He and I consumed the whole thing, broth and all. I became very ill and vomited. I should have known better.

As usual, before bed time a few men would be delegated to dig a slit trench outside the barn for nature’s call. This barn had a loft, and a ladder leading to it. The barn was jam-packed with prisoners on the bottom, as was the loft above. Well, guess what? Packed with prisoners and no lights, it was somewhat easy for those sleeping downstairs, but not for the guys in the loft. I was in the loft. Around midnight, one fellow had to go. He encountered lots of trouble navigating over and around bodies. He stepped on someone. I heard curse words, but otherwise total silence. Somewhat later, another fellow nearby also had to go. He decided not to try what the other fellow tried, and relieved himself the easy way from above. The law of gravity prevailed. I heard the recipient below exclaim, “You dirty S.O.B.! If I ever find out who you are, I’ll kill you!” Total silence for the rest of the night.

We resumed marching the next day. Our accommodations that night were at a church. That was good because it rained that night. Men were sleeping on the floor, as well as in and under the pews. All space was utilized. Next day, no marching. That evening after dark we marched again. It was the dark of the moon. Visibility was nil. During this part of the march, the fellow following you put his hands on your shoulder. You in turn had your hands on fellow in front. Sometime after daylight, our new accommodations, “Moosburg prison,” came into sight. We had been on the road from April 4, 1945 until April 20, 1945. We had travelled a total distance of about 120 miles.

Our new prison camp looked much the same as the one we just left, complete with double barbed wire fencing and the familiar guard towers encircling the area. A few barracks existed, but the new accommodations were mostly tents. I was assigned a tent and the ground was my bed, next to my friend Harry. I don’t remember who was at my other side. I’ll never forget a directional sign on the prison grounds, showing the approximate distance to New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco and other U.S. cities.

This camp was much larger than previous ones, but separated into many different compounds. I later learned this camp housed over 76,000 prisoners of war. Of these, about 6000 were American. Other compounds were represented by nearly every country Germany had fought or occupied. Most were from France, the Soviet Union, Britain and their colonies or from various parts of southeastern Europe.

German rations at this new camp were almost nonexistent – little more than a loaf of black bread sometimes, and bowl of soup occasionally. Thanks to the Red Cross, added to the German fare, we could at least subsist. The Russians received no Red Cross Parcels. The Russian P.O.W.s I saw here were mere skeletons,. Many of them could hardly walk and looked very sad. Russia did not attend or sign the so-called Geneva Convention agreement in regards to treatment of prisoners of war; consequently there were no Red Cross supplies for Russian P.O.W.s.

After a few days at Moosburg prison, prisoners were becoming more aggressive. Everyone, including German guards, knew the progress of the war. We all felt it would not be long now. I recall German war planes including FW-190s, ME-109s and the first jet airplane in the world, designated as the ME-232s, flying treetop level over our camp. I’m sure the low altitude could be attributed to them not wanting to encounter our war craft at higher altitude. Another tell tale sign of progress of the war was viewing our own P-51s and P-47s flying low over the camp, performing tricks, such as dipping their wings, etc. Prisoners were tearing down the fences. Guards just ignored such activities, just keeping to their regular beat. I heard later a few prisoners escaped to downtown Moosburg, tore down the flag and signed their names.

One German guard, while talking to my friend Harry, promised to give him his rifle if Harry would put in a good word to the capturing American troops. This didn’t happen, but it was a good indicator of the low level of morale among the Germans.

On the 28th of April, 1945, artillery was sounding very close and loud. An artillery scouting plane called “Little Elmer,” a piper cub, was also seen over our camp. April 29, 1945, was liberation day. A photo of this day can be found in Tom Brokaw’s book entitled, “the greatest generation.” My feelings and thoughts on this day can best be expressed in a short message I wrote while the battle was going on. I wrote this message on a piece of paper torn off of a Red Cross parcel. I don’t recall where the pencil came from:

George Emerson April 29, 1945May 1, 1945:I can honestly say this is the happiest day I ever remember of. The artillery sounded close all night of April 28. The real fireworks for Moosburg, started about 9: A.M. this Sunday morning and lasted about three hours. A tank and two jeeps just came thru camp. Everyone is wild, P-51’s, and little Elmer have been buzzing this camp all day. What a beautiful sight.Captured Feb. 9, 1945 Eisenberg

Liberated April, 29, 1945 Moosburg, Bavaria

General George Patton came thru camp today. Plenty of U.S. equipment around now. We are getting our first white bread this evening since being P.O.W’s. It looks like angel food cake.

We were liberated, but not yet released to go on our merry way. There was necessary processing, delousing, establishing identities etc., which all needed to be done. . But hey, the food and living conditions had improved, so who could complain? This was the longest single week I can remember, waiting for further orders, etc. Finally, my group was notified to prepare for leaving. We were trucked to an airport near Lanshut, Germany. C-47s were waiting to take us to Le Havre, France. Such happiness, hard to explain. A few hours later we arrived at Camp Lucky Strike near Le Havre France. This camp was American, named after Lucky Strike cigarettes. Their new duty was to further process P.O.W.s returning from German prison camps. Other cigarette companies such as Old Gold and Pall Mall were represented nearby. Regular showers, good food, warmth, partial payday, shopping at the P.X. and the comfort of being within a friendly environment once more. Finally, our time came to ship out. We were taken to a troop ship named the Thomas Berry. We shoved off to the U.S.A.

As Paul Harvey would say, “And for the rest of the story…” What about the B-17 and crew that struck mine on Feb 9, 1945? After my retirement in 1987, I had time to pursue this part of the story. I knew my bomb group number was 303. I was able to access history of mission #313, and all pertinent information concerning that fateful day. The name of the other aircraft was “Pogue Ma Hone.” This name is the Gaelic phrase meaning “Kiss My Ass.” Two engines were damaged. It limped into Poland some 250 miles after the incident over Eisenberg. It crashed near Jaraczewo, Poland. Five died in the crash. Three parachuted safely before the crash and captured by our ally, Russia. They were eventually returned to the U.S. by way of England.

I had the names of the three who survived. In 1994, I mailed letters to each of those via the G.I. Insurance Co. Philadelphia Penn. Harry Shultz. The navigator received his. I received a phone call from Harry in October, 1994. Many letters were written and phone calls ensued. We decided to meet sometime soon. The 8th Air Force was having a reunion in St. Louis, Harry’s home town, in September, 1995. We mutually agreed this would be good place to meet. A surprisingly good time for both of us, we decided to do the 303rd reunion the following year. His wife had passed away a few years before. His daughter, Beverley, accompanied him to the next reunion, and a couple more after that.

Harry’s experiences were many, especially that day of Feb. 9, 1945. Until we were reunited, I had always wondered what happened that day. Was it pilot error or what? Harry clarified this for me. Flak had disabled one engine on his aircraft, thus causing it to plow into ours, disabling another engine. Knowing they couldn’t make it back to England, they chose to head for Poland, and crashed just inside Russian lines.

Harry informed me a memorial had been erected by the Polish people in Jaraczewo, honoring the crewmen who lost their lives Feb. 9, 1945. A real coincidence, the Germans had also erected a memorial to my buddies, near Eisenberg Germany. Harry and I had contemplated visiting both crash sites, but that plan was quashed after his death shortly thereafter.

My wife “Edmee” and I visited both crash sites in July of 2005. We were cordially welcomed by the Polish people in Jaraczewo, and the German people in Eisenberg. This was a very special moment in my life.

AND NOW FOR A FEW WHAT IFS

I’m the only survivor of the Lt. Barrat crew. I suspect I might have been the only crewmember with parachute attached.

That day, Feb. 9, 1945, I had no I.D. or dog tags. Lucky I was captured by civilians.

The allies bombed Dresden, Germany a few days after my capture. Some reports claim 100,000 refugees were killed in those raids. Hitler issued an order, all English and U.S.A. Air force prisoners were to be killed. His subordinates wouldn’t obey those orders!

The B-17 that struck our plane that day, cut through our aircraft back of my position. What if it had struck our plane further back, including right where I had been?

We were flying about 25,000 feet, on oxygen, with electric heaters in use. I was suddenly in space, no oxygen, or heat, but the parachute was open. Who pulled the rip cord? I could never remember.

I imagine there are those who wonder how I can remember all the events that happened after capture. They are still pretty fresh in my mind. Perhaps this is because over the years I have attempted to write this story at least three times, but always gave up. But, here it is now, hopefully some will enjoy it!

I’ve often been asked what it was like to be a P.O.W. in Germany in WW-2. I don’t really consider myself to be an expert on the subject, I was only a P.O.W. for less than three months. Probably best to ask a person who was imprisoned three years or more. However, in terms of what the most difficult aspects of the experience were, I’d have to say it was the uncertainty of my future, and the fact that even though we received Red Cross parcels occasionally, hunger was still a most pressing issue in a P.O.W.’s life on a constant basis.

One thing that still bothers me. When someone finds you were a P.O.W. in Germany, they will often say, “You were lucky to be a P.O.W. in Germany, instead of Japan.” I agree, but I really didn’t have much choice in the matter. When I hear such comments, it makes me wonder what this person was doing during the big one!

[Researched by 303rdBGA Historian Harry D. Gobrecht]